The more than 20 occupations carried out by the Landless Workers' Movement (MST, in Portuguese) on Red April 2024 reveal a disturbing reality: not enough progress was achieved in the struggle for land reform since April 17, 1996, the date of the Eldorado do Carajás massacre, which has now become World Day of Struggle for Land.

Twenty-eight years ago, a camp was set up at Curva do S, in the town of Eldorado do Carajás, in the southeast region of Pará. Around 1,500 people planned to march to Belém, Pará’s capital city, where they would demand that the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra, in Portuguese) expropriate the Macaxeira farm, occupied by 3,500 landless families.

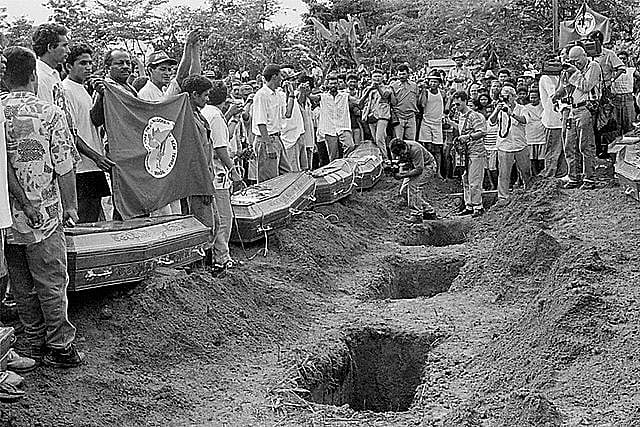

The march was never finished. On Wednesday night, the group was surrounded by military police officers who violently murdered 21 landless rural workers and left another 79 injured.

The tragedy became internationally known. It inspired works of art, boosted the establishment of a date of struggle and put pressure on the Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Brazilian Social Democracy Party) government, which created the Ministry of Agrarian Development and the National Program for Education in Agrarian Reform (Pronera, in Portuguese) the following year. It was extinguished under the Temer and Bolsonaro governments, respectively, and resumed under Lula’s third presidential term.

It is in honor of the victims of the massacre that the MST and other popular movements are promoting, in April, days of struggle for land, dubbed Red April.

Current conflicts

In recent years, the number of conflicts in the countryside has increased, with new challenges in the fight for better land distribution in Brazil.

This year, Invasão Zero (Zero Invasions, in English), a group investigated by the Federal Police for acting as a rural militia and suspected of involvement in the murder of an Indigenous leader, released a booklet in what they called "Yellow April" against "land invasions".

"This escalation [of violence] by landowners deserves coordinated action by authorities since there is a political, economic and criminal arm of this entity that needs articulated, national, federalized responses, especially for attacks on settlements, Indigenous territories and other traditional communities," said federal prosecutor Julio Araújo to Brasil de Fato.

Another new obstacle for grassroots movements in Brazil’s countryside was a package of laws put to a vote in Congress, an attempt to curb and make it impossible for organizations to advance their agendas. Among the measures to be voted on is the end to the need for a court order to use police force to remove land occupiers; a ban on the payment of social benefits to members of occupations; and the mandatory creation of legal personality for movements intending to act politically.

"We're talking about bills that want to destroy social movements. They want to make democratic action impossible," said federal deputy Patrus Ananias (Workers’ Party, Minas Gerais state).

In the face of adversity, the MST issued a statement highlighting the actions carried out this April and reaffirming its quest for popular agrarian reform. "We are fighting because 105,000 families are camped out and we demand that the federal government comply with article 184 of the Federal Constitution, expropriate unproductive estates and democratize access to land," said the movement.