“Former soccer player Pelé said he may run for president in 1994. He said he considers himself a socialist and intends to start a political party if he decides to run for office." It is difficult to believe that, at some point in history, the two phrases abovementioned were the headlines of one of Brazil’s biggest newspapers, Folha de São Paulo. But it indeed happened.

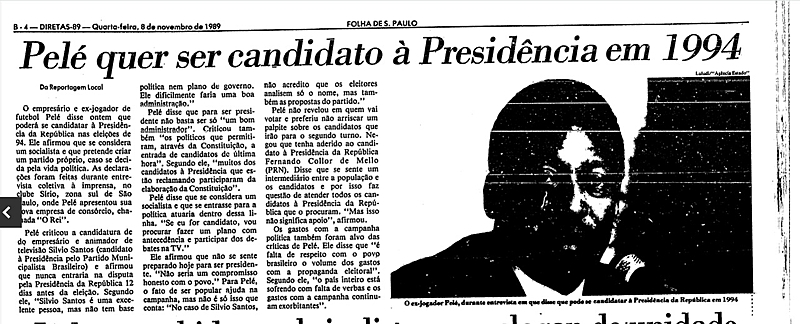

On November 8, 1989, in the eve of the presidential election that led up Fernando Collor to the presidency, the newsstand across the country showed a peculiar headline: “Pelé intends to be president and says he is a socialist," reads the lower cover page of Folha de São Paulo.

The statement was made the day before that, November 7, during a press conference hosted at the Syrian-Lebanese club, south region of São Paulo. In the occasion, Pelé presented a newly founded company called “O Rei” (The King, in English). Despite this, due to the impending presidential election, the main subject was one that the former player rarely discussed: politics.

At the time, the then TV host and businessman Sílvio Santos was still insisting on launching his candidacy with the Brazilian Municipalist Party to run against big names in Brazilian politics, who ended up being candidates, such as Lula (Workers’ Party), Leonel Brizola (Democratic Democratic Party), Ulysses Guimarães (Brazilian Democratic Movement) and Mário Covas (Brazilian Social Democracy Party). Days later, the Brazilian Supreme Electoral Court vetoed Santos' plans, the owner of SBT TV network. Pelé criticized Santos presidential intentions.

"Sílvio Santos is a great man, but he has no political base or government plan. He would hardly make a good administration," he stated. In another moment of the conversation with the journalists, he said: "If I'm a candidate, I'll try to write a plan in advance and participate in the debates on TV." Pelé was questioned and declared himself a socialist and said that if he entered politics, he would act within that ideological line.

The fact attracts attention because the "King" never wielded the banner of socialism. It is true that, five years earlier, in 1984, Pelé had taken a stand in favor of the Diretas Já campaign (campaing asking for direct voting during the military dictatorship in Brazil), to resume elections for president. In 1969, he dedicated his 1,000th goal to "poor children". Even so, the former player was never associated with the left, not least because he was marked by the relationship with the Military Dictatorship that ruled Brazil during the country’s third championship, in the 1970 World Cup hosted by Mexico.

"Pelé, the king of soccer, with the Diretas Já t-shirt, a movement for democratic opening, in the mid-1980s. The photo was taken at the PPG complex (Pavão, Pavãozinho Cantagalo) in Rio de Janeiro. The idea for the photo came from a joint effort by photographer Alemão and Pelé. The idea was to print magazines and show the King of Soccer's support for redemocratization. Despite having traveled all over the world, this image is hardly disclosed because, according to popular imagery, Pelé never had a significant political commitment. The memory remains. Text – @joelpaviotti"

There are no records of criticism by the media after Pelé declared his socialist positions and presidential intentions in 1989, even though speaking badly about Pelé is one of the favorite sports of Brazilians.

In an excerpt of his autobiography published in 2010, he explained the political content of his statement after the “1000th goal”. “I think that many people didn’t understand what I was trying to say [about poor children]. I received some criticism; people called me a demagogue. They thought I wasn't being honest. But it didn’t bother me. I believe it’s important that people like me send messages about education. There won’t be a future if children aren’t educated," he wrote.

Years later, in 1995, he took on the exceptional Ministry of Sports during the government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Brazilian Social Democracy Party). In just over three years of heading the ministry, Pelé embraced the modernization of soccer and the guarantee of labor rights for professional athletes. Due to his decisions, he earned the enmity of FIFA's João Havelange.

He was also behind the Pelé Law, which changed the prior situation in which soccer clubs were guaranteed athletes' contracts. It also caused the professionalization of soccer clubs' departments, which began to pay income taxes.

In the same press conference, Pelé did not say to who he would vote that year’s presidential election. He has not even made sympathetic statements to the Workers' Party candidate Luiz Inácio da Silva or to the then-socialist politician Roberto Freire. He denied that he was supporting Collor and said he felt like a mediator between the people and the presidential candidates.

At the beginning of 2022, I tried to contact Pelé’s press office to comment on that interview from the late 80s. Since his health was already debilitated, I couldn't hear his current thoughts about his statements. The “King” left this story as another element of his relationship with politics – an element that shouldn’t be ignored.

Folha de São Paulo’s cover, November 8, 1989; in the bottom half, the headline draws attention to Pelé’s statements. Image: Folha de São Paulo’s collection / Reproduction / Folha de São Paulo's collection

Article published by Folha de São Paulo newspaper on November 8, 1989. It highlights Pelé's electoral intentions and mentions socialist inspiration. Image: Reproduction / Folha de São Paulo’s collection.

Article published by Folha de São Paulo newspaper on November 8, 1989. It highlights Pelé's electoral intentions and mentions socialist inspiration. Image: Reproduction / Folha de São Paulo’s collection.